Irish Arts Review

Autumn 2019

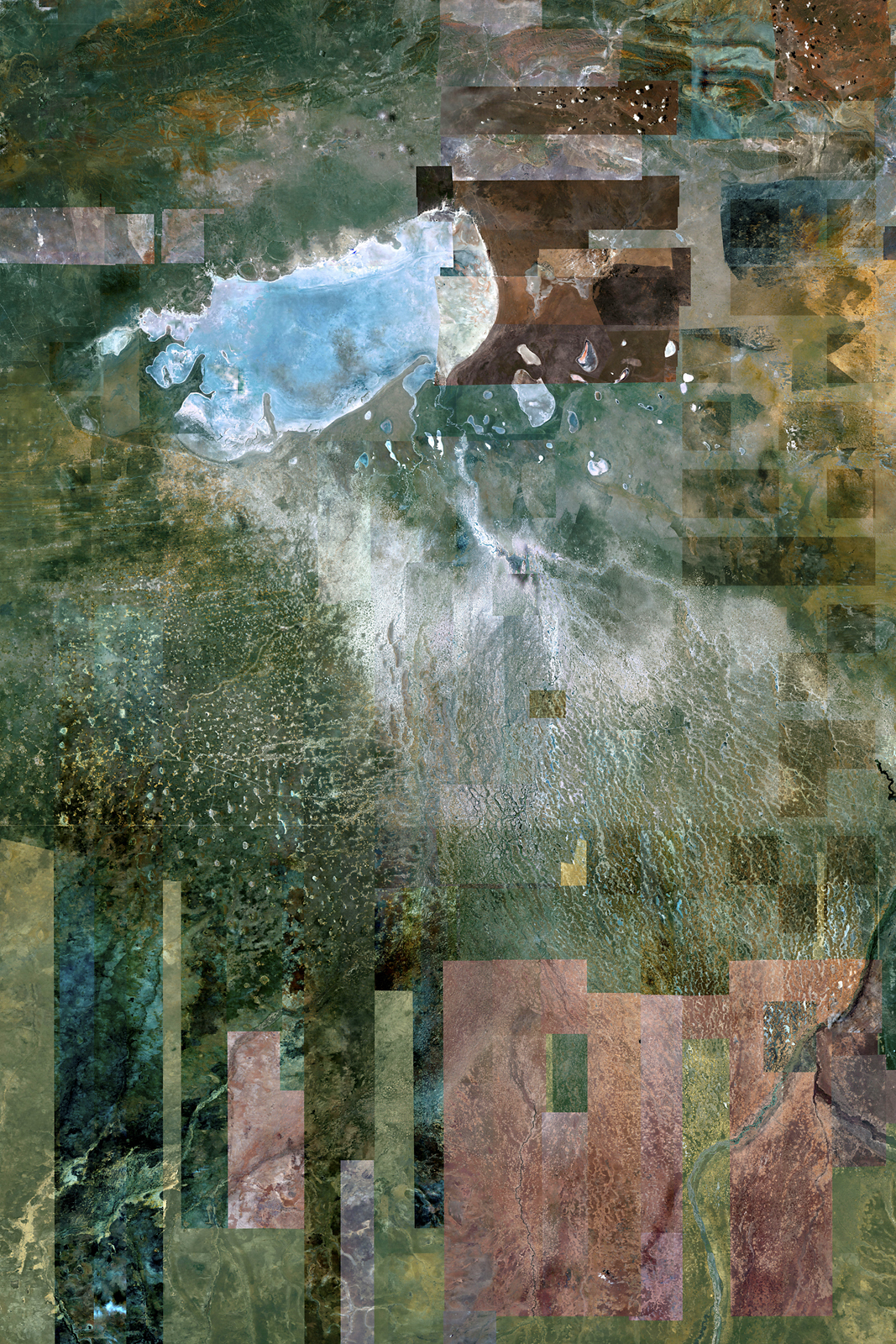

Using satellite imaging, photographer David Thomas Smith echoes the Arecibo radio message transmitted into deep space forty-five years ago, writes Stephanie McBride

One slice of Hong Kong’s waterfront is so popular among photographers that, over the past decade or so, it has become known as Instagram Pier. It provides the background for tourist selfies, fashion shoots and wedding photos, yet often the photographers are trying to reimagine or recreate much the same image – the same panoramic harbour view; the same skyline or sunset; or the same configuration of old lamp posts, oil drums and cargo pallets that they have seen online.

Full Article: Irish Arts Review

Archive footage of Arecibo at The Copper House Gallery as part of the PhotoIreland Festival 2019.

Video by Cian Brennan

Conscientious

Photography Magazine

It is not a new thing; indeed at the present it seems a positively over-done thing. Appropriation of Internet photography -specifically from Google street-view or Google maps- is acutely prevalent in current photographic and art practice. It may be said that there is far too much imagery littering both our virtual and actual environments already, and to react to this by producing yet more images only adds to the glut of imagery that is being critiqued in the first place. However this seeming contradiction of agendas can be beneficial to the work of a few. In order to make work that critiques the very thing that it eventually embellishes, the work must conceal its agenda behind deliberate layers of intersecting imagery and absolute conceptual rigour. The work must have entire conviction that it is not just another Google project.

David Thomas Smith’s work Arecibo is a project that combines appropriated Internet imagery with an exploration into the history of humanity and evolution of civilisation. Using naturally occurring fallout colours from the creation of Google Maps, Smith uses thousands of jpegs to construct an image of a significant period in human history. Smith’s images, laced with the Arecibo message (a message broadcast into space in 1974), can be seen as the latest phase in human evolution where nothing is beyond the reach of documentation, publication and appropriation. Smith’s work addresses the evolution of humanity whilst being acutely aware that in creating this work, he is participating in the cutting edge of human civilisation. An abundance of imagery we may have created, constructing it in our own image we are guilty of too, but Smith, in a kaleidoscope of absorbing colour and form shows us how we have arrived at this current chapter in the history of humanity.

- Christopher Thomas

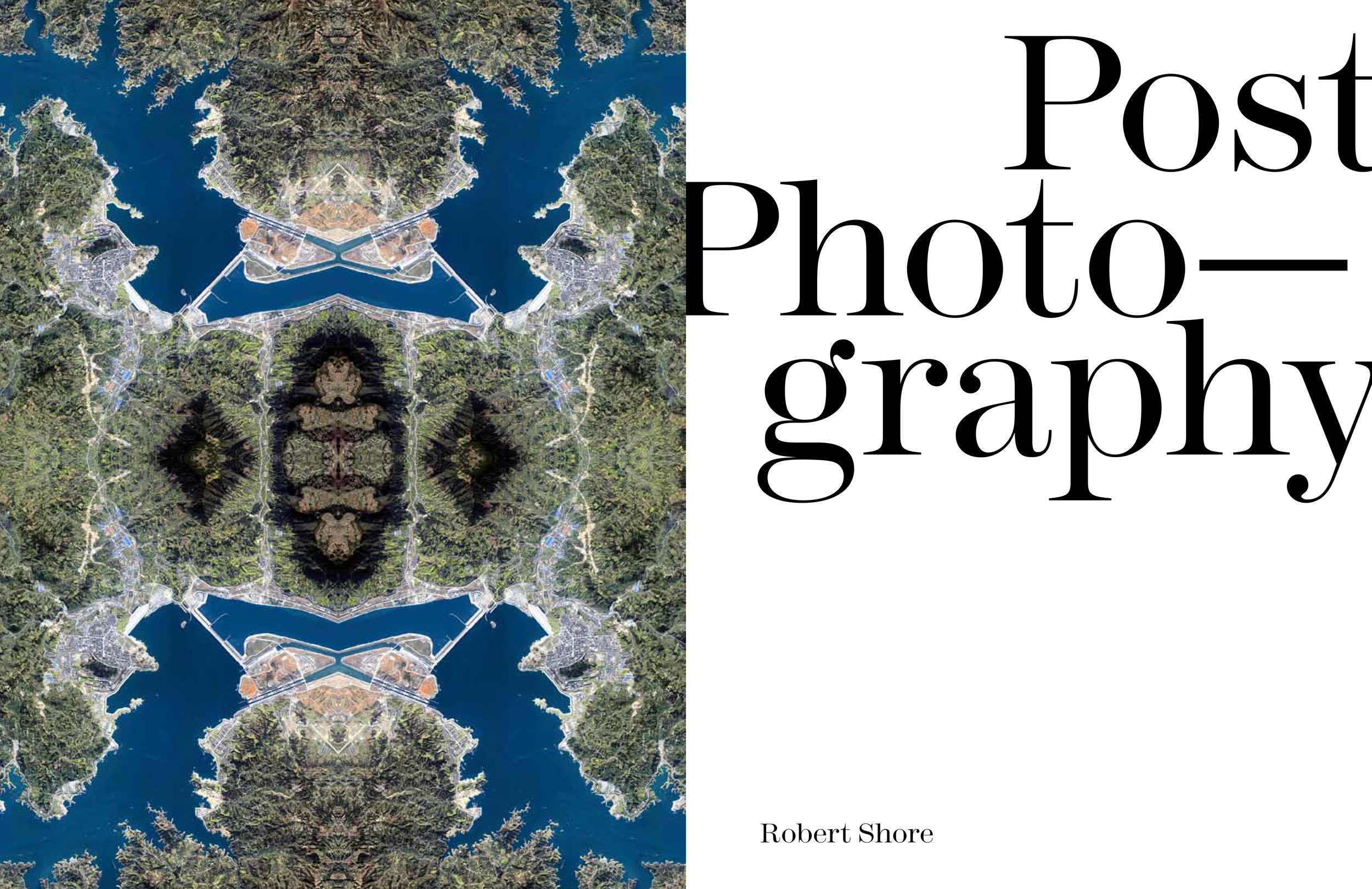

Post-Photography

The Artist with a Camera

Esquire

Issue 77

GUP Magazine

Guide to Unique Photography

“In his series Arecibo, Dublin-based photographer David Thomas Smith (b. 1988) pays visual homage to that original message, and reflects on the birth of humanity, our growth and evolution.

Smith constructs his series on the basis of nine significant moments in human history, from the location of the birth of man, through the bronze and iron age, to its current in-progress state, the information age. Each image is created as a composite of thousands of JPGs from Google Maps, showing landscapes of an evolving world from an extraterrestrial scale and viewpoint. The resulting images are distorted by changing patterns of light, both natural and man-made, as well as Smith’s encoding of the Arecibo message itself in the images. Seen from afar, both in time and space, we are left to ponder humanity’s development as one small species in an infinite universe.”

- Katherine Oktober Matthews

New Irish Works II

PhotoIreland Foundation

Selected by an international panel of 23 professionals, New Irish Works brings you a selection of 20 projects and 20 photographers representing the diverse range of practices coming from Ireland.

New Irish Works 2016 is a year long project of 10 presentations and 20 publications that aims to highlight the great moment Irish Photography is experiencing.

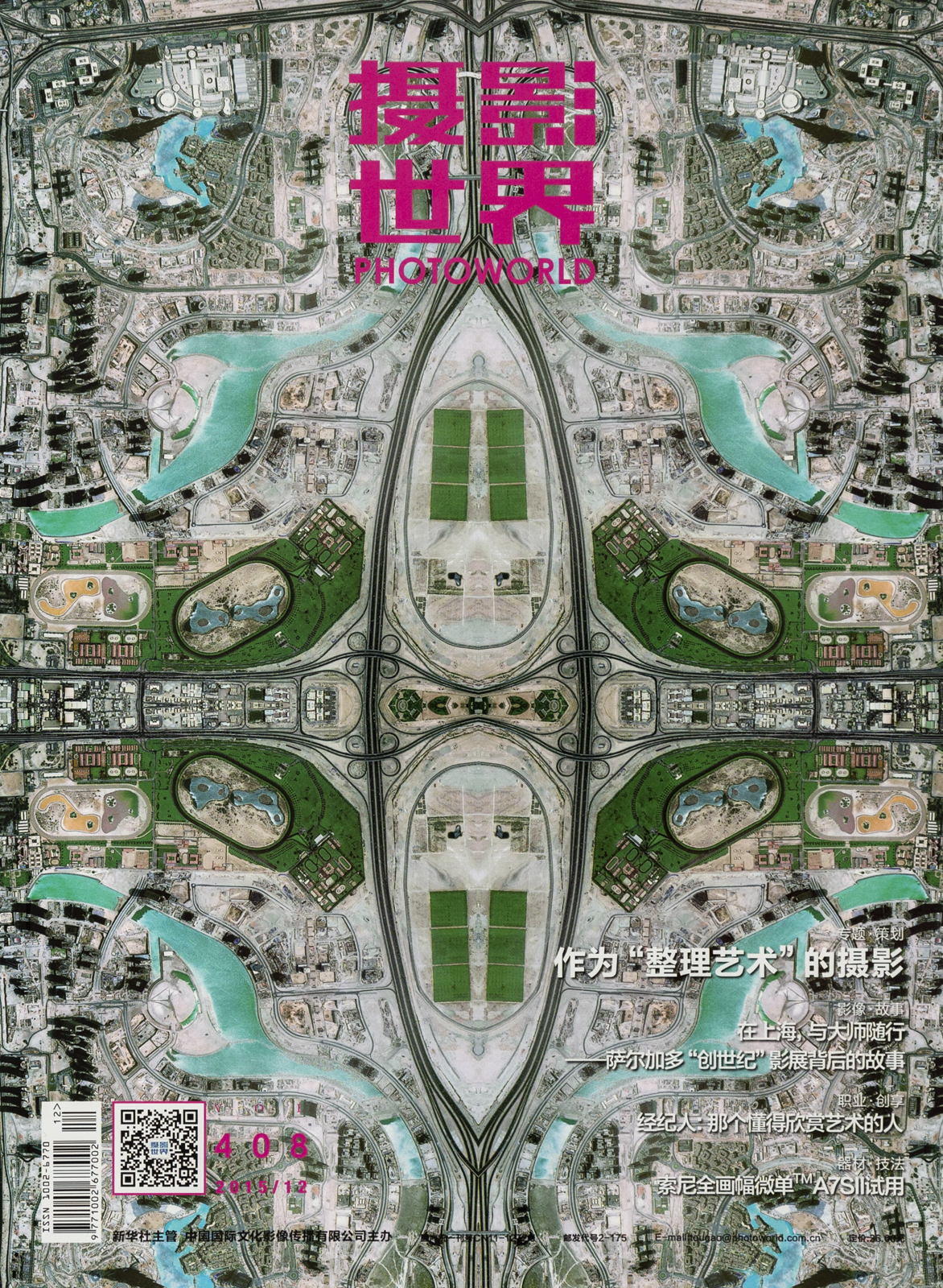

PHOTOWORLD

Issue 408

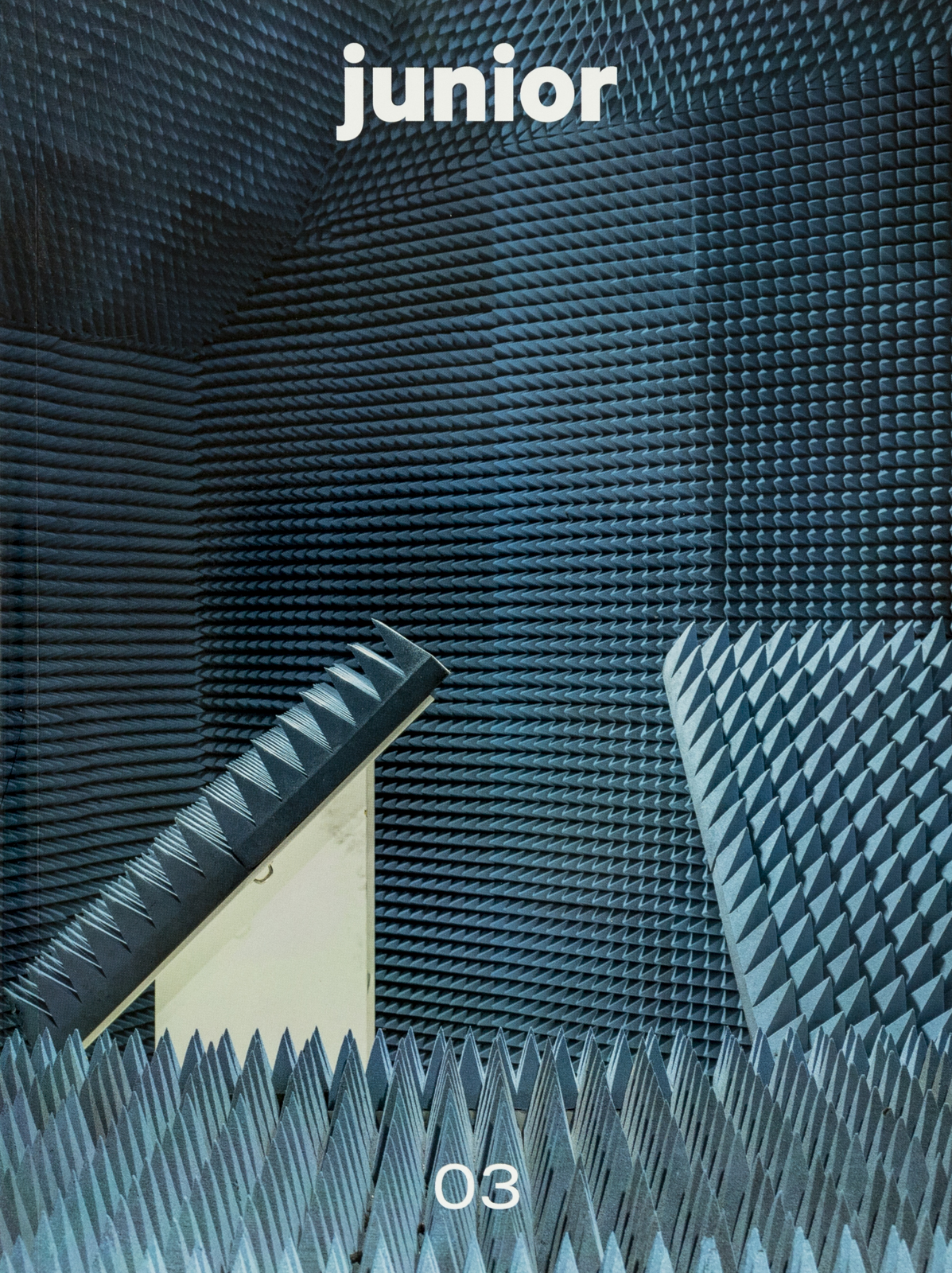

junior

Issue 03

IMA

Living With Photography Vol. 9

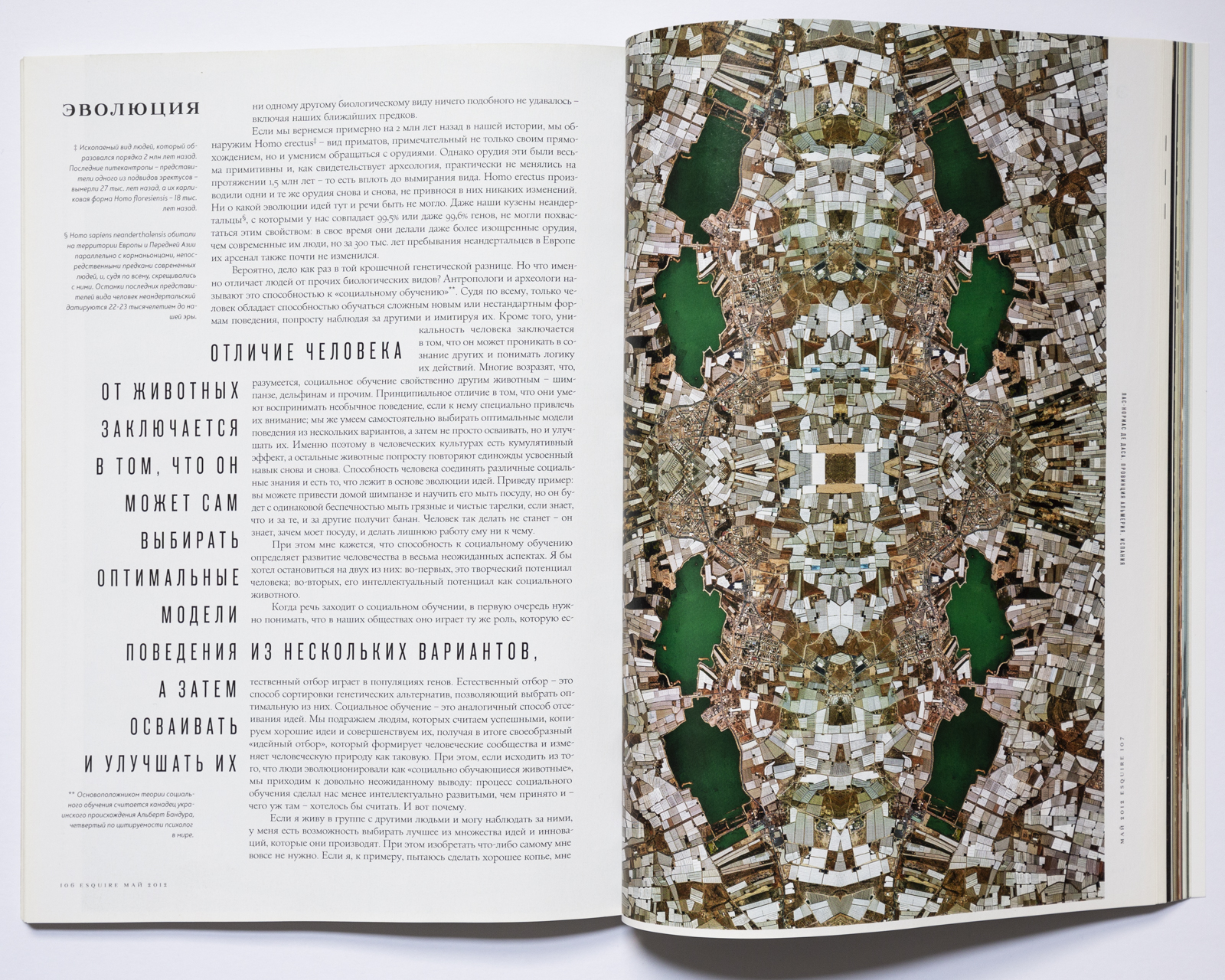

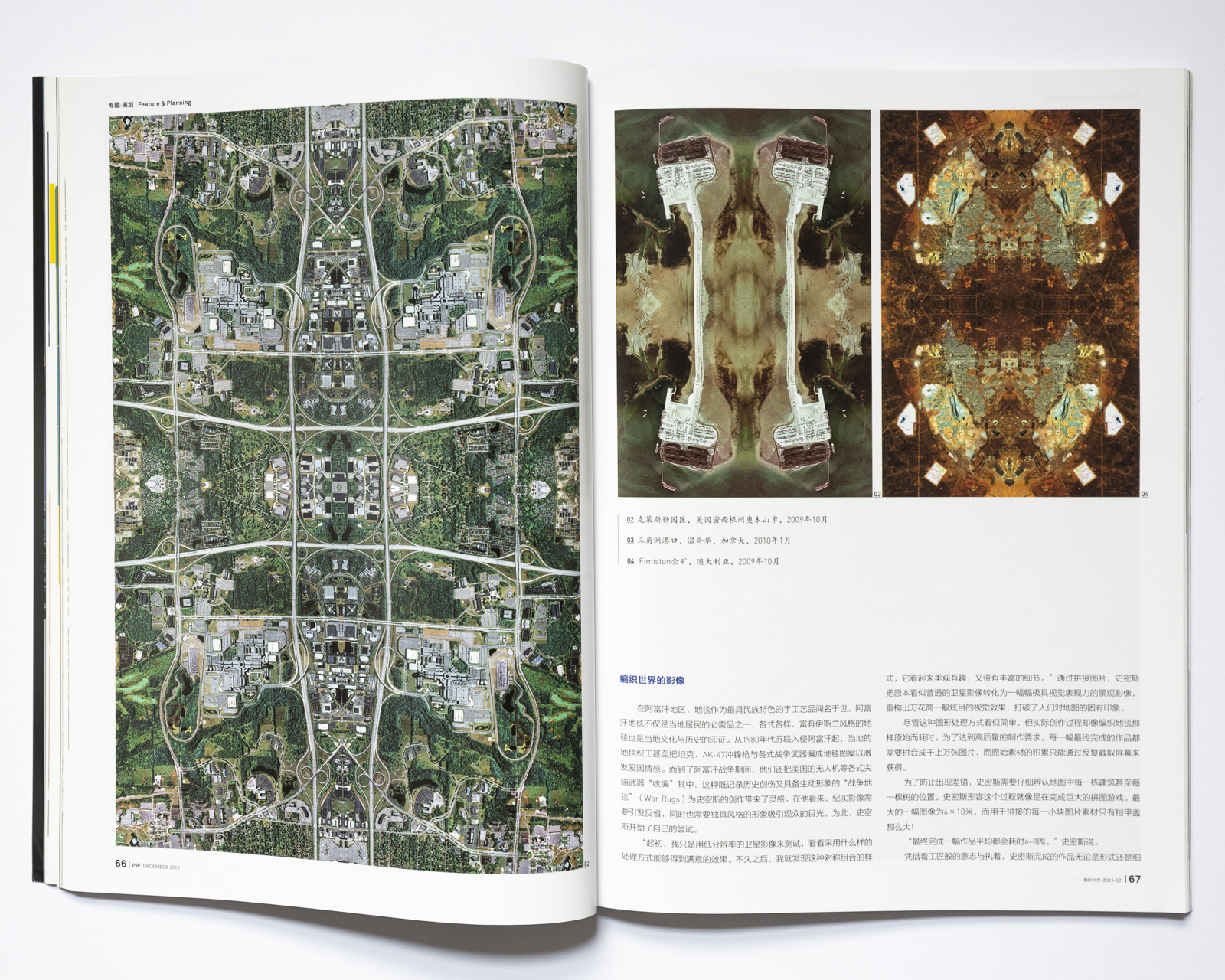

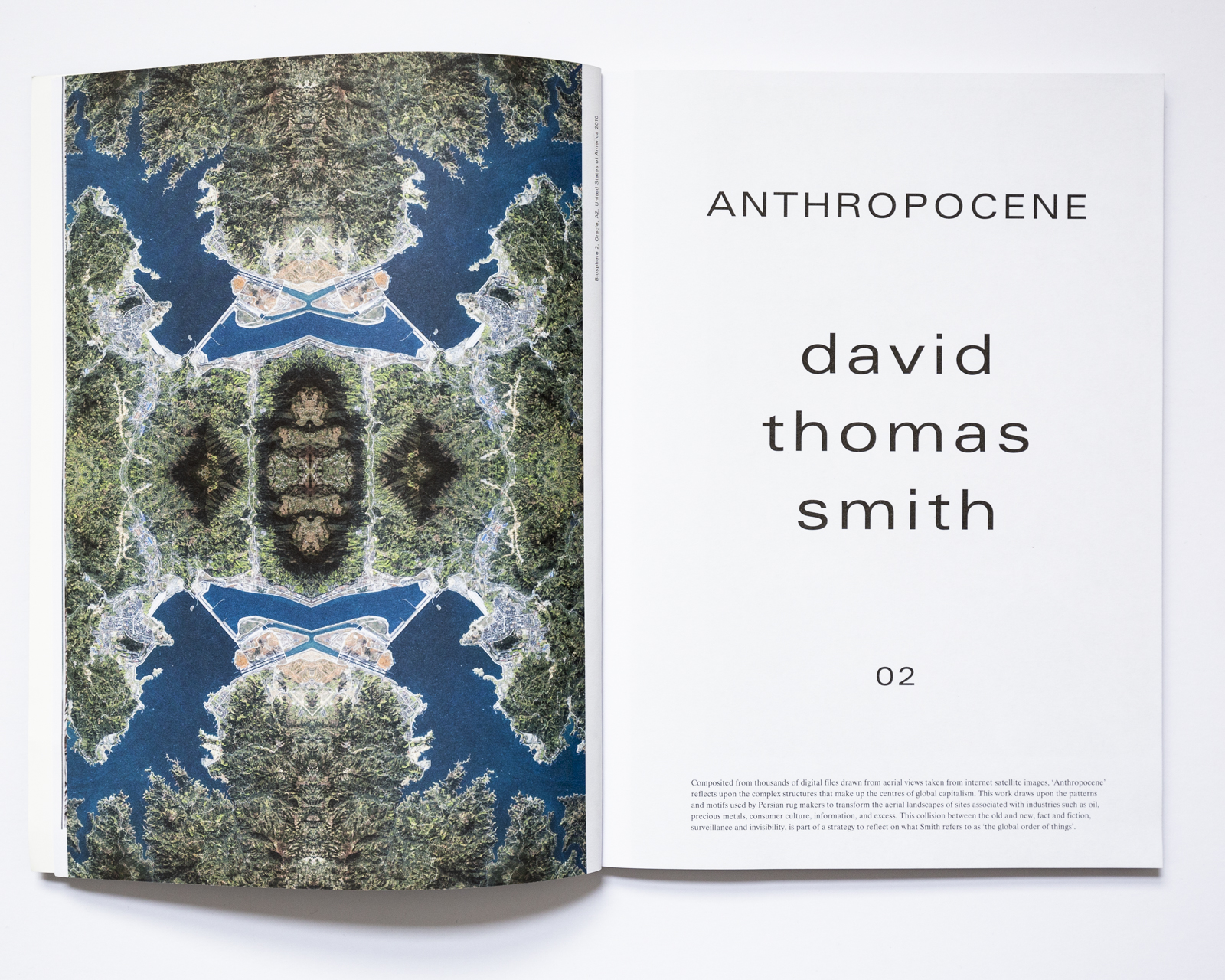

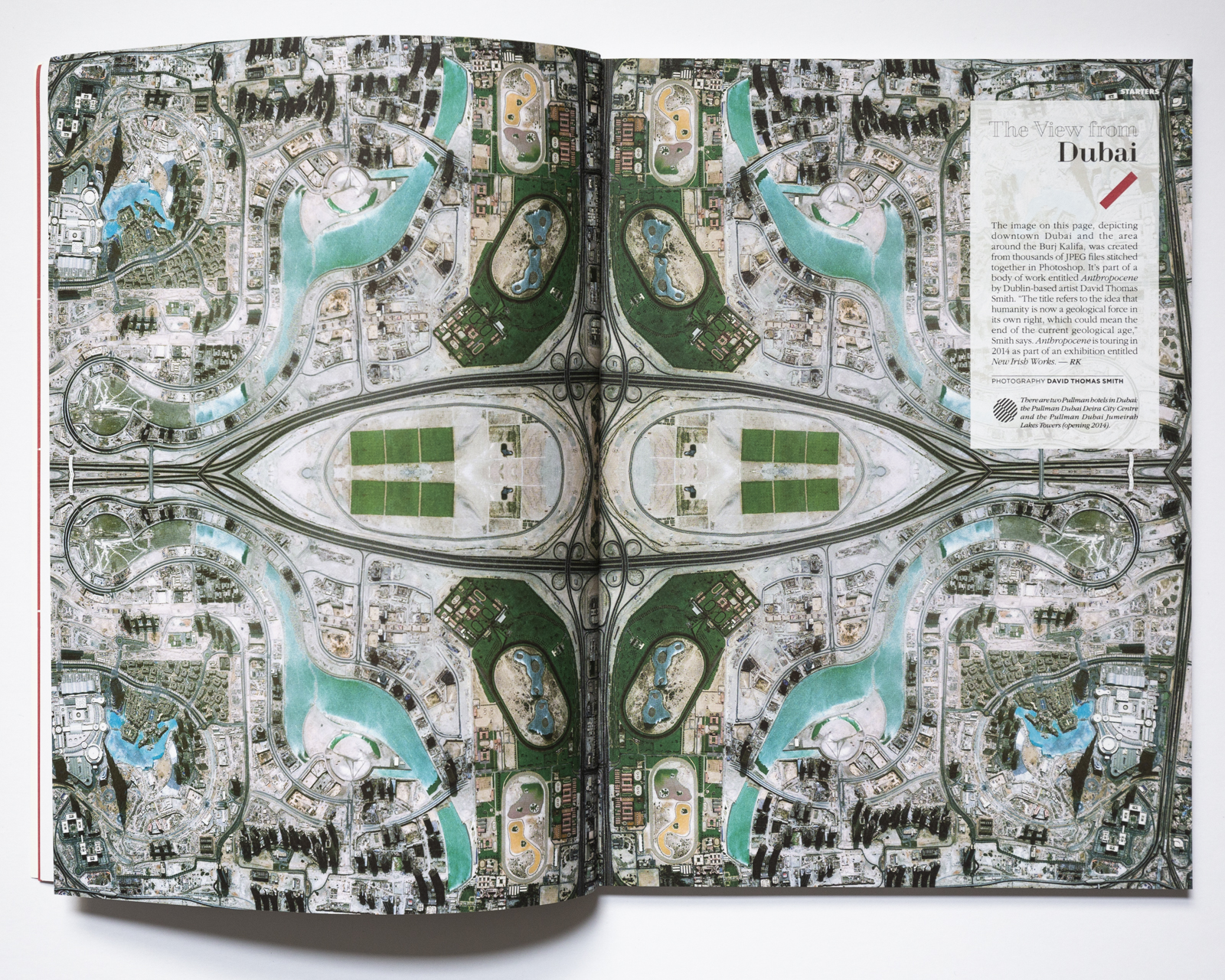

David Thomas Smith’s photographic series ‘Anthropocene’ was recently exhibited at The Copper House Gallery in Dublin. The photographs are digitally assembled from a large number of Google Earth images which depict some of the world’s most recognizable manmade structures and urban landscapes. The satellite images are then both vertically and horizontally mirrored to create a visually striking tapestry effect. The similarity to a tapestry is reinforced by the large scale of the work and also by the inherent ‘flatness’ of satellite images of the Earth.

Crucially, each location alludes to specific environmental concerns: ‘Three Mile Island’ relates to the threat of a nuclear meltdown, ‘Beijing’ perhaps points to a rise in pollution while the opulence of ‘Las Vegas’ questions our relationship with consumption. Other images equally refer to social problems specific to a place: the urban displacement caused by the Three Gorges Dam or the exploitation of cheap labour in Dubai. These references are produced not necessarily by the image as such, but by an understanding of the place that these images represent.

The title of the project ‘Anthropocene’ is a geological term that describes how human activities have had a significant impact on the Earth’s ecosystems. The images similarly allude to the ecological and social impact of vast manmade structures. As a whole, the project questions man’s ability to create a better and more sustainable world at the cost of dwindling natural resources. Andreas Gursky – in his photograph ‘Beelitz’, 2007 for instance – might be exploring a similar agenda in his vast photographic depictions of landscapes affected by consumption and excess.

In as much as the project relates to ecological and social tensions that rise in parallel to globalization, the mirroring of satellite images also relates to ideological, political and economic power. In the first instance, the project alludes to the power of representation. Satellite imaging and mapping is dominated by Google. To a large extent, our understanding of how the world looks may not be controlled by Google, but it is certainly dominated by the ever-growing economic might by the corporation.

In the second instance, the symmetrical structure of the images divided into quarters also relates to ideological power. Governments and religious institutions have historically tapped into the persuasive powers of symmetry in their architecture. Churches are usually divided into four distinct parts, while dominant symmetrical structures are used to reinforce the ideological authority of the state. An overhead view of Margaret Thatcher’s funeral at St. Paul’s Cathedral recently published in the Guardian vividly illustrates the coming together of visual symmetry and aesthetics, on one hand, with political and religious structures, on the other hand.

This reading of Smith’s work is promoted through images that are neither didactic nor patronizing. The work could be enjoyed for purely aesthetic purposes. Yet it could also be seen to relate to some of he most pressing ecological and social issues of our time.

– Marco Bohr

SIR EDMUND

de Volkskrant

The Pullman Magazine

Issue 02